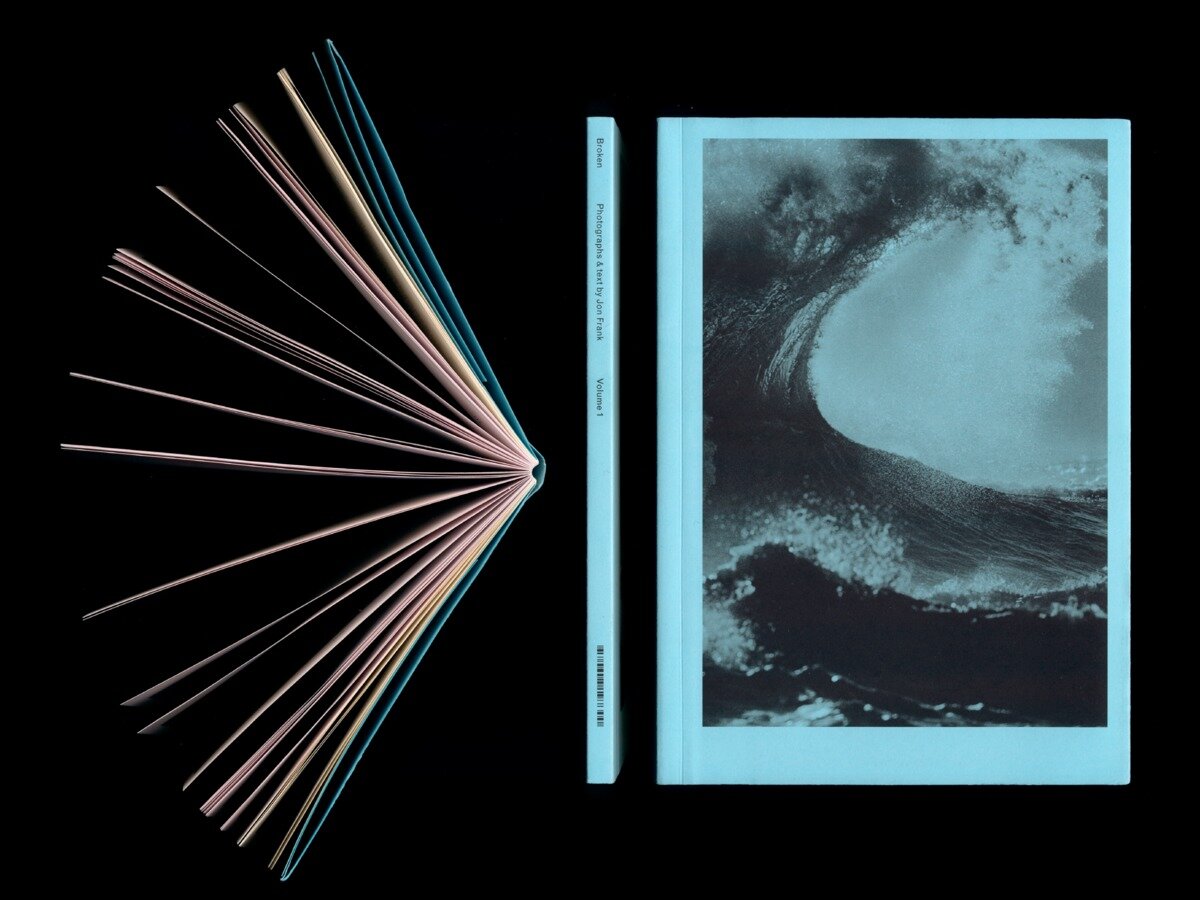

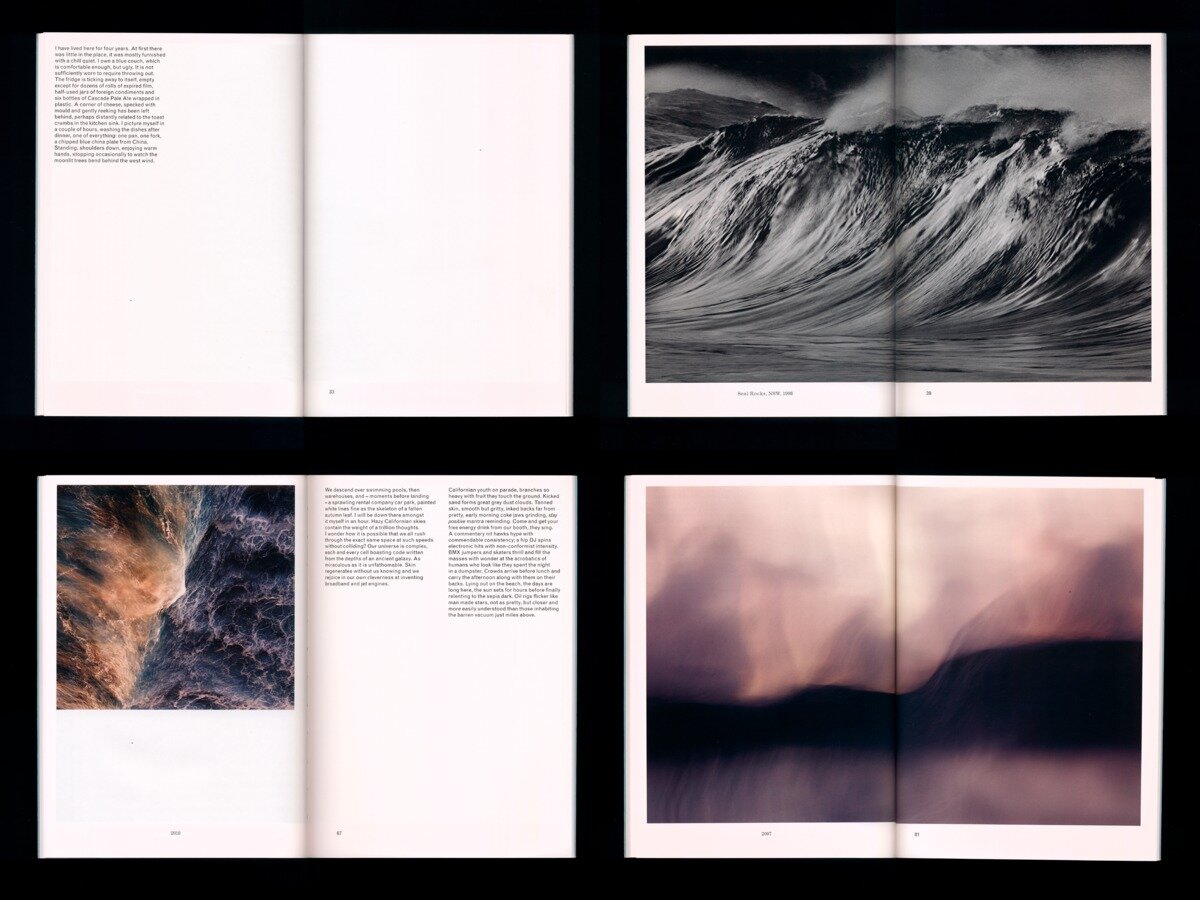

Broken is a book chronicling twenty-five years of ocean photography and writings (published 2017).

Jon Frank - Broken by Sam Rhodes.

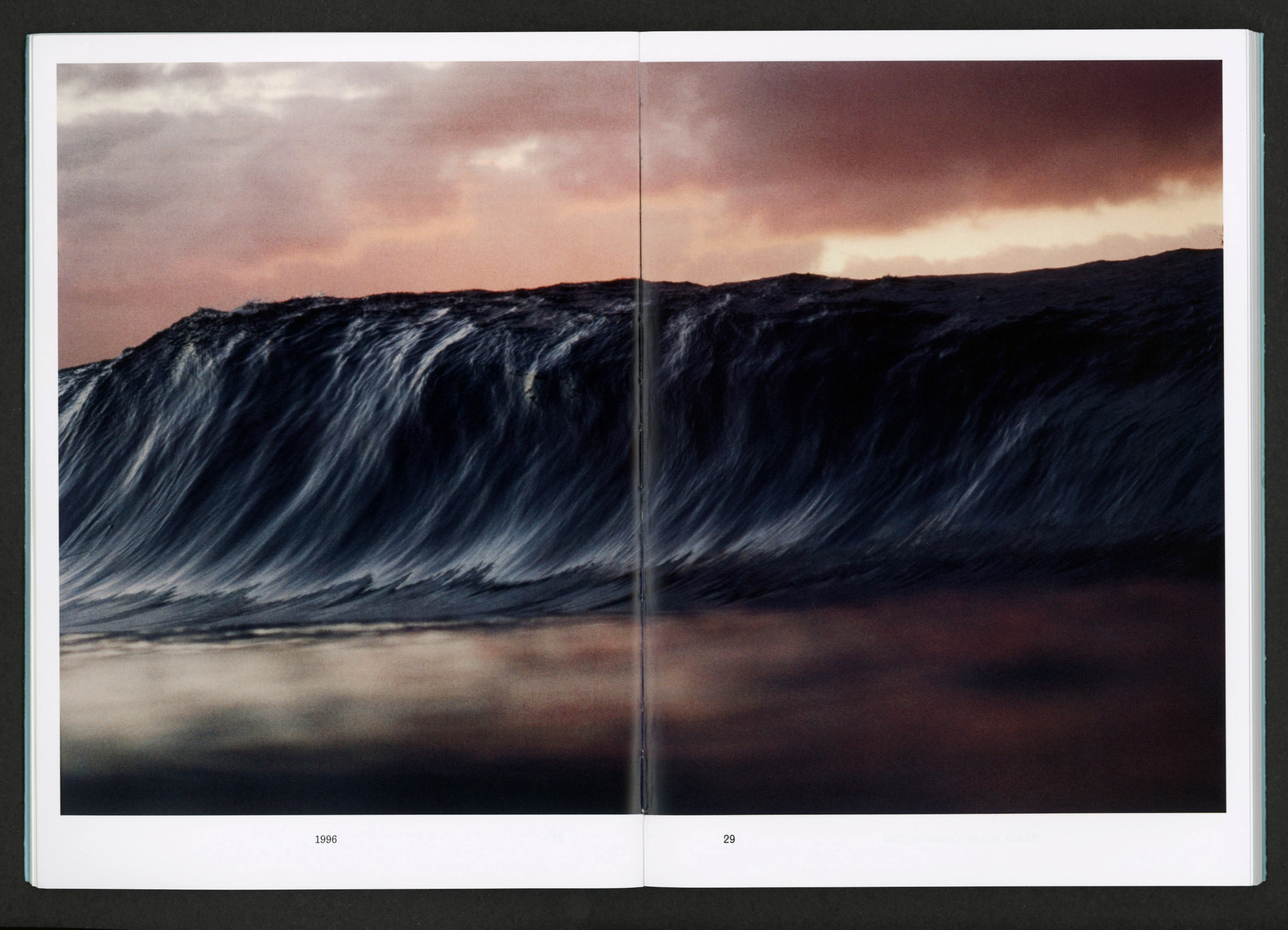

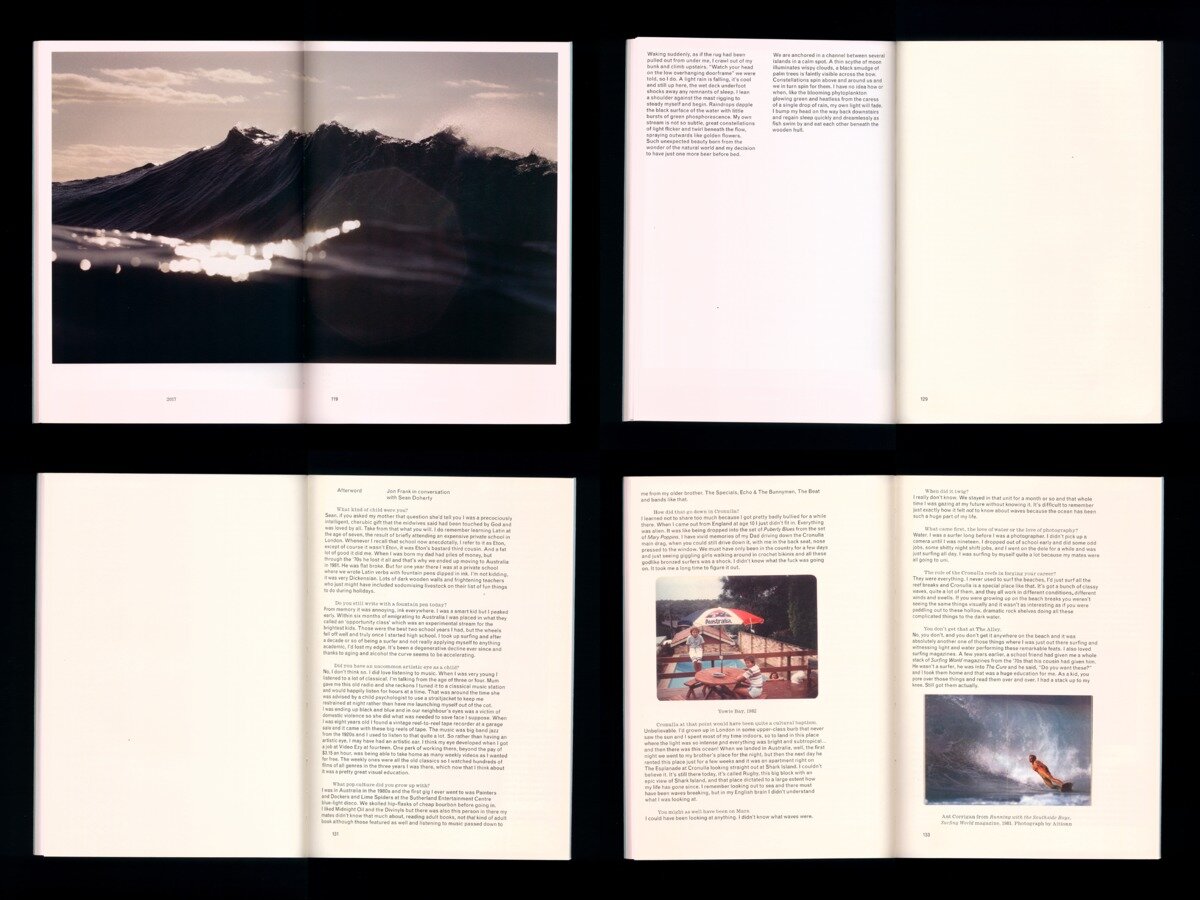

Over the years I have considered Jon Frank’s images to be documentation. The results of a person who has learned the ocean, navigated to its specific places of concentrated beauty, and captured the sum of the moment in a single frame. But looking through Broken - I think they are something else. They are less tangible than this logical explanation. I may be at risk of sounding contrived, but I consider Frank’s images to be documentation as transcendence. They represent their subject but are also mysteriously abstract. A photograph is in its nature an abstract document: A two-dimensional portion of reality that can never actually be what it represents, no matter how accurate the depiction. They are translations of differing eloquence. Most often photographs amount to less than their moment of reality, small disposable imitations. But occasionally they become something else - maybe something more. Such is the case with Jon Frank’s images.

As I think about trying to neatly articulate my response to Frank’s images in writing I can’t help but wonder if it is a wasted objective. The core of a response to an image is non-verbal, it is an immediate and un-justifiable reaction. The use of words to rationalise the reaction is an additional process - an afterthought that becomes complex, wordy, arty and often overly intellectual. The seeing of the image itself is very simple. It is a direct sensation. Bliss, calm and confusion are a few words I would attribute to the seeing of Frank’s photos. But for the purpose of this article I must elaborate, translate the nuances, articulate the experience. Maybe I have been cynical. Maybe this is the ultimate objective as a writer. To express in clear language what feels inexplicable.

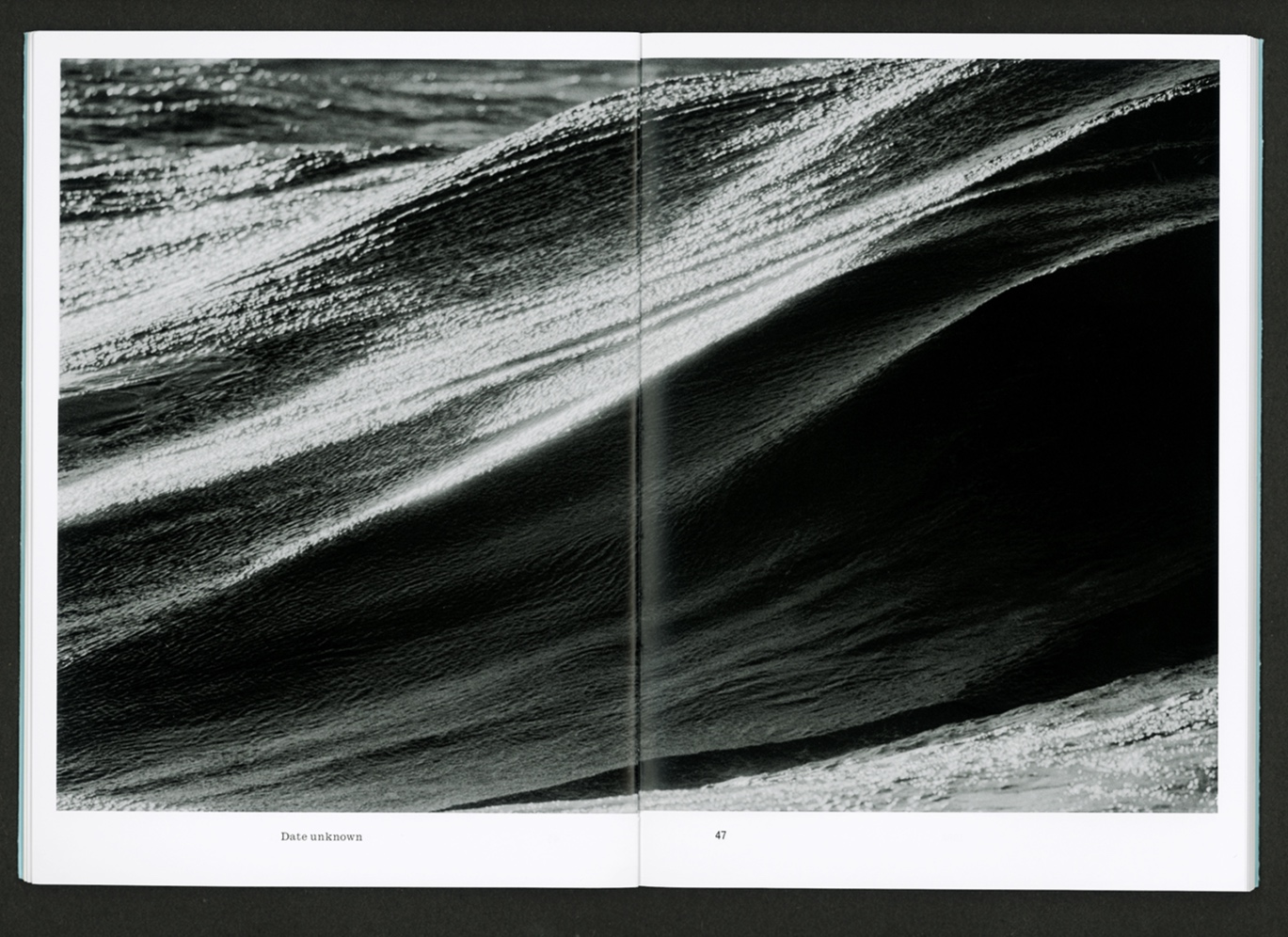

I want to say that meeting Jon adds something to his photographs, but it feels counter intuitive. They are not personal statements. They are pure access to what lay beyond the lens. In saying that once you have seen one of Frank’s photos another one is instantly recognizable. A Jon Frank image could only have been taken by Jon Frank. I suppose the only conclusion I can draw from this paradox is that both he and his photographs have what I can only describe as a gentle touch. Jon has a strange way of making a shot of an 8ft shark island slab feel very calm, a peaceful image of a threatening moment. There is a kind of still-silence about the images. A separate-ness from the intensity of their situation. This is the nature of their abstraction. But at the same time, you are right there, fully immersed. They are moments purely distilled. They feel enter-able. They lead to a strange feeling that if you kept looking for long enough you might finally see something that is hidden beyond the image.

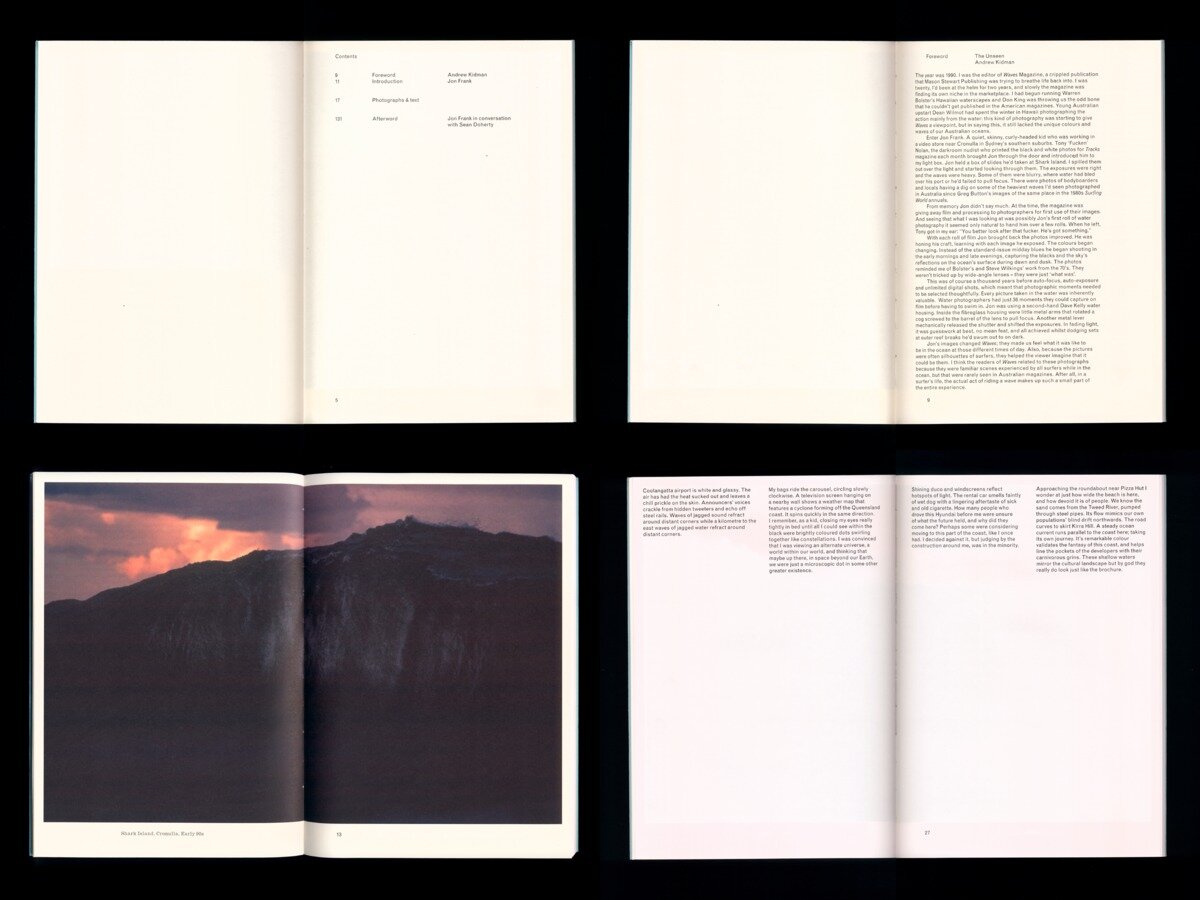

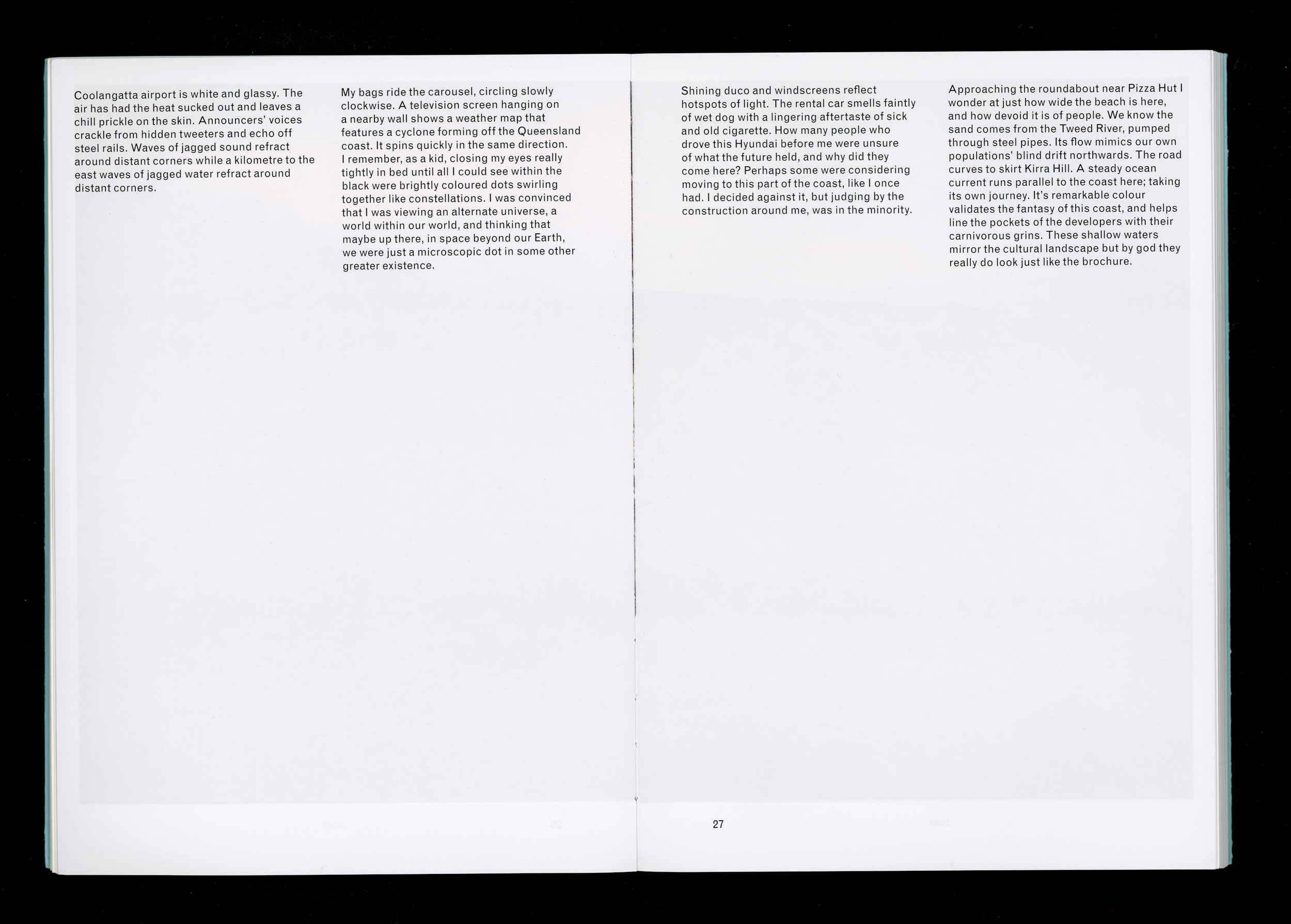

Jon’s writing, which is included throughout the book, reveals a sensibility that extends beyond the sea. He describes Tasmania as ‘a mute witness to evolution’. The Atlantic Ocean as ‘Ancient, creased grey felt’ and Coolangatta airport as ‘white and glassy’. At the end of his written introduction to the book he talks about one of his first jobs converting super 8 home movies to VHS videotape. Watching for hours as tapes of Christenings or birthdays ran through a rudimentary telecine machine. He writes that he was often bored but on occasion ‘transfixed by this intimate window’. It’s funny, when I look at Frank’s photos I too feel ‘transfixed by this intimate window’. I sat down with Jon to talk about Broken. He is considered and incredibly self-deprecating.

Interview:

How did you find the process of selecting images to be included in the book?

It’s a really difficult proposition to edit your own pictures. You can invest quite a lot of energy into a picture, it’s good to have someone who’s not invested in them to just go ‘No that’s shit, that’s not going in’. So, editing is difficult, and what are you trying to say? As an artist or a photographer who puts books out, why are you putting this thing into the world? Is it vanity? Is it because you think the world needs it? are you trying to change something in the world? Is it a political statement? Is it just art? Which is enough of a reason in itself. Maybe art brings people pleasure? Maybe that’s a good enough reason? Maybe it makes people think about things? Art can do all those things, good art. Or maybe it’s just pretty? Looks nice on your wall, there’s nothing wrong with that too. So, when your editing for a book you kind of have to go through all this stuff, and most of the time at the end of the day if you really think about it long and hard you probably wouldn’t even do one (laughs), you talk yourself out of it. So maybe the moral of the story is... don’t think too much! Good pictures they slap you in the face. The answers always there, you’ve got to feel it and not think about it too much. There’s a lot of feel anyway, you get it wrong. I get it wrong a lot, but you live with it. That was a long answer.

I noticed looking through the book that your written extracts are never directly related to the image beside them?

Yeah, I mean what are you gonna say about a picture of a wave? “Oh yeah I went down to the beach and put my flippers on swam out and the wind was whipping off the back of the wave, it was zephyr” (laughs) I dunno. I mean what amazes me is surfing magazines, how people can still be writing about the act of riding a wave ten thousand issues later. Surf writers must be some of the greatest bullshit artists, how do you write about surfing? For 50 years, every month, on and on, their genius.’ Although obviously things have changed over the years, surfing keeps evolving for better and worse. I mean when I was a kid you would never dream of the waves these guys are surfing these days, it’s a completely different realm. I don’t think anyone even twenty years ago ever imagined these waves would be getting surfed… you know who did though, Mark Foo. The day before he went Mavericks and drowned, he called me up and said “Jon I’ve got this idea, I just want to go out into the open ocean, I think there’s gonna be really big waves out there, 50 feet waves”. At that time that was just an unknow realm. This is probably 20 years ago, he knew there was something out there and now of course there’s waves like Jaws being surfed and the slabs and all that, it’s amazing. But then on the flipside we’ve got the advent of the wave pool which is like the antithesis, for me. It’s a way to commodify further something that has been very commodified. I don’t even need to go down that road suffice to say that I don’t think it’s good. Well I don’t actually think its surfing, they’re saying, “we’re gonna get surfing in the Olympics, and we’re gonna put it in a wave pool” well it’s not surfing. Surfing is in the ocean, surfing is about being in the ocean, that’s what it is.

In the book you say for a photo to succeed it needs to transcend its medium, what did you mean by that?

I stole that, that’s not my quote, I wrote it in the book like it was my quote, so I could sound intelligent, but I ripped that off Bill Henson. What he means by that, when your standing in a gallery looking at a photograph, you should forget that you’re looking at a photograph. What I take from it is it’s like when you’re listening to really great music in a good environment, you lose yourself to it and you forget where you are. Maybe that’s what joy is? It happens when your surfing sometimes too. Sometimes you get those moments when you look back on the session and you can’t actually remember anything specific, maybe that’s what he’s talking about? That the effect of what your experiencing overrides the thought process’, the analytical side of the brain, maybe it’s something like that.

Do you think it’s hard to analyse or rationalise images using words?

Oh yeah, it’s fucked. It’s like an artist statement, have you ever tried to write one of those? What a crock of shit, they’re unbelievable. It’s just art speak. You’ve got to go to art school to be able to speak that language and understand it, or pretend you understand it. Nothing turns me off more than reading an artist statement. If you can’t get what the works about just by seeing it… I want to feel my own feelings, that’s what it’s for, don’t tell me what I need to read into this picture, I’ll figure it out for myself and if I don’t get it ill draw my own conclusions. Half the time the artist doesn’t know what the work is until after the works finished anyway. Art history, like any history, it’s all just made up. Look at the history of Australia. You look in the history books that I was taught when I was at school about white Australia and about how it was settled, you know, the great land, the sheep’s back and all that, and then you look at the genocide that was committed on innocent people whose land this actually is. Compare the two stories and there’s actually no correlation at all. They’re different planets. But one is the ‘history’. Only now, 220 years later are we starting to actually get the other side of things. People are starting to become aware of what really happened.

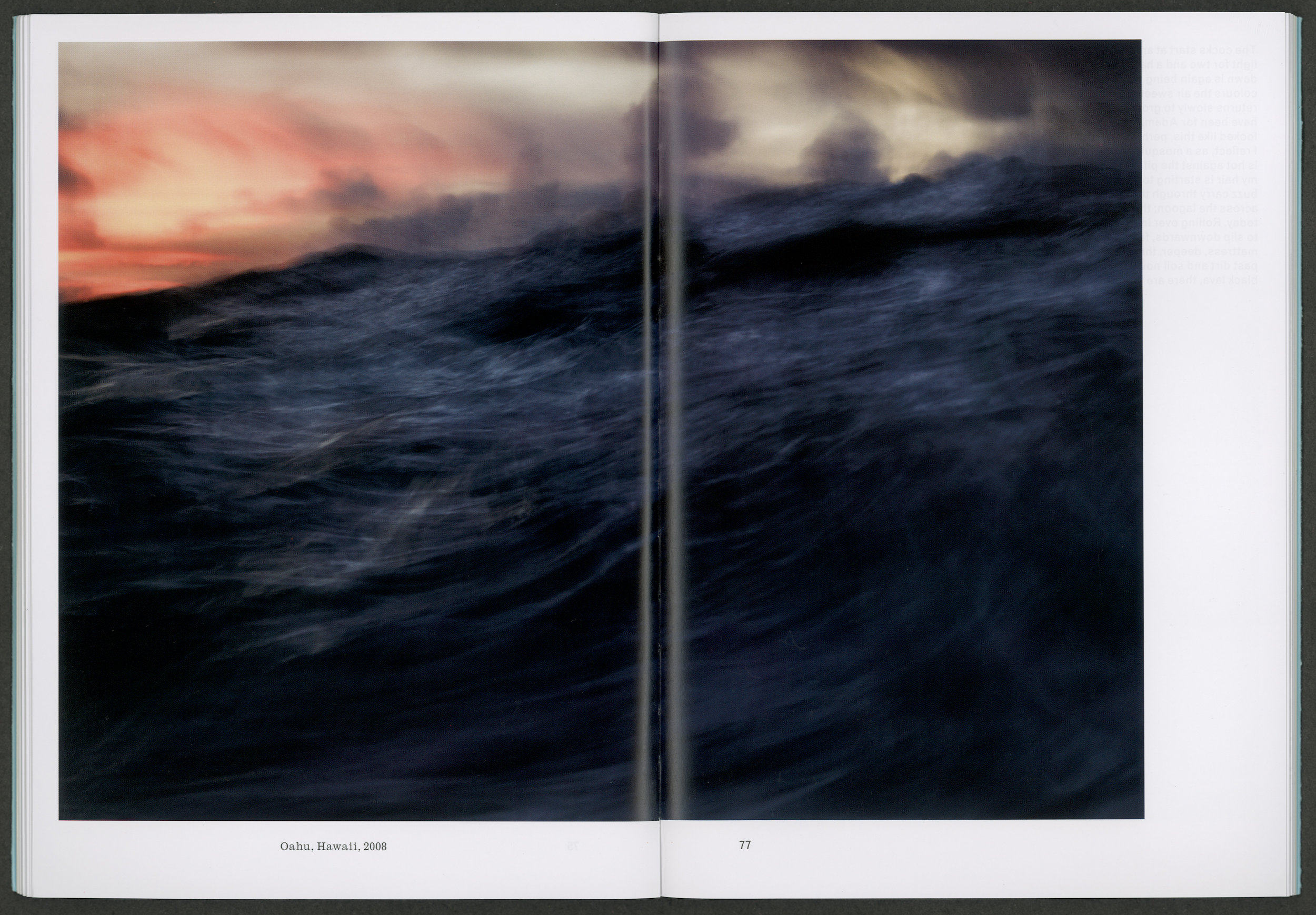

The photos in the book often have this calm, blissful feeling, and then you realise that it’s actually an 8 ft slab at Shark Island, an intense situation. Do you feel calm taking shots in those intense moments?

Most of the time when you’re shooting, you’re in less danger than if you were surfing, you don’t have to position yourself too close. I mean there are certain times shooting very wide angle when you can get caught, but most of the time you’re not in any imminent danger. So yeah you can get caught. But any swimmer knows most of the time it’s an advantage to not be tethered to something that floats, like a surfboard. You can go underneath waves, you can open your eyes, you can see where the dark spots and the light spots are, the dark spots are the turbulence. There are those times when you think your going to drown, you get shaken up a bit. But that’s just being in the ocean, that’s not unique to photography.

Can you think of a specific example of getting in one of those situations?

There have been a lot. Pipe one year was quite big, and the beach was packed with photographers, there were probably 50 guys all standing in a row, this would have been late 90’d early 2000’s. It must have been the pipe masters or something, I can’t remember. I swam out where you do and got completely obliterated. By the time I got to Gums, I was puffed and I got taken. I kept getting sucked into the impact zone. At the end of the wave there’s this really shallow sand bank, and I kept getting hammered (laughs). Eventually I got deposited way down the beach near rocky point somewhere and then had to walk back in front of all the photographers who would have been watching, and laughing probably, it’s pretty funny, you do the walk of shame and try again. By that point you’re so puffed but generally on the second go you get out. Most of us photographers are surfers, so we understand the water and the waves. But we’re not the fittest creatures, the older you get you think maybe I shouldn’t be jumping out there because you’re not in the greatest shape, but you always get through it (laughs).

What about writing, how do you find the experience of writing?

Oh, writing is just… it’s sadistic. I write really short sort of…. I don’t know what you would call them, self -indulgent (laughs). I dunno, it’s not prose, it’s like a poem for someone whose not a poet, so it’s probably just really bad poetry but all in running sentences, it’s quite descriptive.

Narrative poetry?

Narrative poetry, that sound good. It’s basically a cop out because to write well is a skill that I don’t possess. Although people often tell me I really like your writing, and I wonder if that’s ‘for a photographer you’re a really great writer’ or whether it’s just maybe that the words and the pictures make each other seem better. Or maybe I can write those little short things. But I’m not a writer. To be a writer you have to be able to really write a poem or a novel. I don’t know how people do that, it’s horrible, writing is pain. Because I guess it’s like photography, most of the time what comes out is really shit. I mean that’s what it’s like for me. I suppose some writers might just bang it out and it all comes out great. I guess it depends what your aiming for too. It’s like photography, or anything, your trying to get to a place…. Martin Amis called it ‘the war against cliché’, we’ve all seen it all before. But we can still be moved by an image, why and how is that even possible? And how will it continue to be?

You talk about working with surf cam images in the book?

This goes back to the conversation we had the other night about the series of painting your dad is doing of Coastalwatch frames. They’re amazing, I think that’s awesome. There’s all this stuff now about AI and it does relate to photography. I’m not too well read on all this, but I really want to investigate it. But surf cams, is that AI? Not really, but it’s still a machine, some of them move, some of them sit still, there’s spray over the lens, there’s just something fascinating in the surveillance aspect of it. I think what I like about it most is that it’s not manufactured, it’s not someone going out wanting to get this great picture. It just like this is what it is, and this is on every day of the year. It’s the monkey with the typewriter, eventually they’re going to come up with something amazing, and they do. The camera that’s sitting on a post staring at the same crappy view all year has moments of absolute beauty.

Do you ever know the image you want to capture before you capture it?

Most of the time there will be some sort of idea of what you want to achieve but that goes out the window when you’re in the real world. With waves it’s all chance really. But if your there and you know the lights going to do a certain thing and you’re going to manipulate it in a certain way then you’ve got a pretty good idea. But then the world will throw something completely different at you and that’s probably when you get your best pictures. But with my other photography that I do which is more just photographs of people, just going about their daily lives, it’s quite candid. People in the world, working, holidaying, whatever. You can’t really ever have any idea of what you’re gonna get. There’s no way you can predict the random nature of what you see. Those photos are purely a reaction to what happens, often very quickly, in front of you when you’re walking around. If you wait long enough the world can go about its business right in front of you, and for one second there will appear this amazing harmony.